Uncivilizing Digital Territories

This piece has been updated since its publication. Last updated: 13 Dec 2023

There’s something fundamentally wrong with the dominant culture, which has become the default despite its direct conflict with the essence of being human and being part of planet Earth. This system has colonized much of humanity with tools that centralize power, a natural tendency for animals like us, but one that does little to foster diversity in gender, spirituality, culture, or to support planetary survival and quality of life.

It’s tempting to think that it’s always been like this: One culture to control them all. However, historical evidence suggests otherwise. Human settlements, rural or urban, did not invariably lead to social freedoms' loss or the emergence of ruling elites. Documented cases of early cities show minimal evidence of social hierarchies, and some cities that began hierarchically later adopted more egalitarian systems .

Despite being the reality for most people on the planet today, analyzing humanity solely through the lens of militarized, hierarchical, and coercive cultures can be overly narrow. This perspective simplifies the complexity of human societies and overlooks the existence of non-dominant forms of organization .

We seem to be at the apex of the capitalist civilization model—power is more concentrated than ever, manifesting in the collapse we witness today. The modern state’s origins are not deeply rooted, but are instead tied to colonial violence. They prompt us to rethink our development trajectory and the normalization of violence and domination within the dominant system.

“We know that Mother Nature has a culture, and it is a Native culture” Yupiaq scholar, Oscar Kawagley

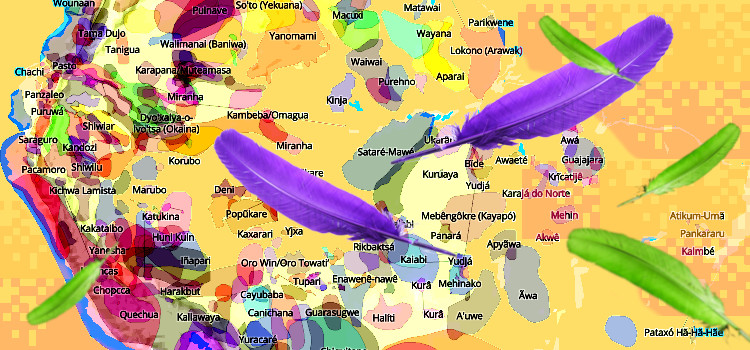

Pockets of resistance persist, enduring campaigns by states, for-profits, and even civil organizations aimed at their extinction and assimilation. Indigenous communities, often at the frontlines of environmental defense, are disproportionately affected by climate change, yet they receive the least support. From the vantage point of diverse communities from different ethnic groups and territories across Brazil, something has become evident: In stark contrast to the domination-based model of civilization, many of these cultures still thrive in harmony with their larger ecosystems, fostering systems of abundance similar to forests. By collaborating and engaging deeply with these cultures, Indigenous practices demonstrate that living with cultural and biological diversity is not only feasible but also vital for long-term survival.

We, the so-called civilized, have been raised to see ourselves in relation to nations built on stolen land, mass genocide, and the exploitation of life. Yet from this limited perspective, can we choose to build tools of solidarity and community over individualism and coercion?

Digital technologies are a double-edged sword. They connect distant loved ones and facilitate learning but also turn people into dopamine addicts and spread disinformation . But they also have the potential to strengthen communities and support their resistance. In this piece, we’ll be exploring some inspirational examples and thoughts on ways to engage with technology in a more communal way.

I have been engaged for years with the community-networks movement and organizations like Coolab and Digital Democracy . We develop communication and information technologies in close collaboration with local communities. By recognizing and understanding the particular needs and cultural traits of a diverse range of territories in Brazil, we can create practices, software, and hardware that align with their values.

Methods of Engaging

There are different ways communities can engage with the digital world. Most often, that first happens when Internet service providers reach out; but, in many cases, it’s not profitable for those companies.

This exclusion leads communities to seek access to communication and information tools themselves. At times, the assistance comes from the state or satellite companies, which are interested in control and profit respectively, not really caring how the corporate web can negatively impact communities.

Photo via Luandro

Experiences of living day-to-day within community networks and sharing those insights with broader regional and global networks enrich the collective management and co-creation of communication and information technologies with local communities.

We continuously learn from each other about innovative methods to engage with communities, participating in their assemblies in ways that are both enjoyable and insightful about the workings and potential impacts of the technologies they are interested in.

A powerful approach is to collaboratively map the territory, using it as a foundational reference for understanding and planning. This allows us to trace the paths data travels through various network transports and to illustrate who ultimately controls it by comparing different corporate and local services. Tech Cartographies is a great resource to help materializing the cloud .

It’s crucial to facilitate a communal understanding of how the community currently perceives itself and its collective aspirations, grounded in their values and needs. This shared vision becomes the starting point for designing their digital territories.

Typically, in workshops or setup scenarios facilitated by external trainers, the community is equipped with the essential elements to cultivate a community-led project—an alternative to the conventional, individualistic consumption of technology. The evolution of this foundation into a thriving collaborative network is a path the community may embark on, necessitating commitment and internal leadership to navigate successfully.

For those interested in learning more about methodologies for integrating technology with communities, valuable resources are available from the Earth Defenders Toolkit Seed Bank and Redes por la Diversidad, Equidad y Sustentabilidad A.C. .

Community-First Interaction Flows

Today’s corporate platforms drive user experiences to become highly personalized, globalized, and market driven—systems which work to deteriorate local governance, cultural identity, and respectful connection to land.

A very common problem, especially within traditional communities, is the disconnect between generations. Traditionally, elders have always held a key role in community governance, extra-community politics, and preservation of stories and ancestral knowledge. When youths start interacting with social media, this sort of archival work is threatened; the information that only elders can transmit is often left aside in favor of whatever is mainstream on commercial platforms such as Facebook or Youtube.

These services do create opportunities for networking, but because of their corporate nature, this usually happens for the benefit of an individual or sometimes a small group but hardly for the community as a whole. That makes it hard for community values to be transported to the digital. What could a community-first user experience look like?

Nature-based communities have been for centuries flooded with alcohol incentivized by corporate and state actors interested in their land and resources; and they were raided by religious conversion campaigns interested in civilizing them. These have been extremely efficient weapons of cultural assimilation and disruption of community autonomy and self-governance.

Unfortunately, it’s becoming rare for communities to be tied primarily by cultural identity. But what every local community has in common is the connection to a physical territory, even if there’s no deeper cultural connection to the land.

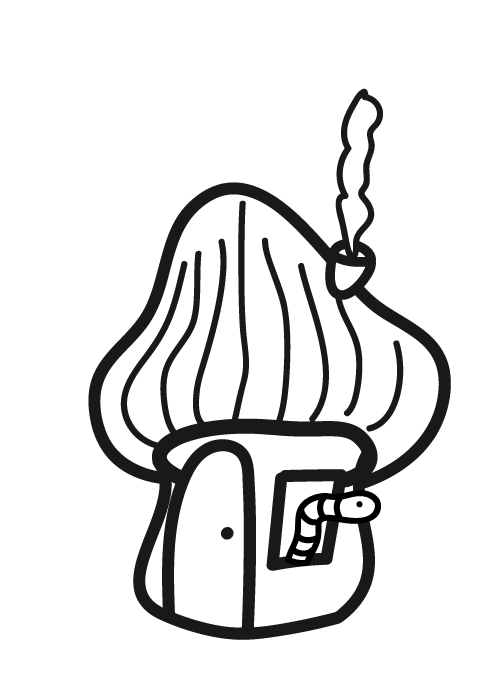

Image via Coolab

By bringing back the focus to the land itself, we can counteract the erosion of cultural identity, enhancing the sense of community and autonomy. Identifying with our local environment fosters a natural sense of belonging.

Our approach to constructing community-first user experiences involves emphasizing the connection people have with their territory. Rather than prioritizing user-centered content, we highlight the community’s land, its people, and cultural expressions. However, having outsiders designing user flows for a community they are not part of can compromise digital autonomy. Just as many communities have their own bakers, they should also have their own digital artisans.

While programming languages and frameworks are more accessible than ever, the dream of community members independently building digital territories to reflect collective needs may still seem distant. This is often due to language barriers and the prevalent low levels of tech literacy in land-based communities. However, the emergence of AI and natural language interfaces, along with the machine’s ability to generate code, could significantly reduce the complexity of programming. This technological progression promises to make software development increasingly accessible to rural communities in the global south.

Local mechanics and electricians are commonplace in communities as hardware can be dismantled, with parts analyzed and reassembled. This tactile learning process requires nothing more than curiosity—a resource often found in abundance in communities. We envision a similar approach for software: utilizing self-hosted web-based code editors, such as Coder , to enable those with curiosity to modify, break, and construct with code.

By making source code openly available for community members to experiment with, and eventually integrating natural language processing and AI assistance, we can foster an environment where individuals could learn to build, maintain, and refine these applications and services themselves.

Image via moinho.app

In Moinho, a community in central Brazil, for example, a market service has been developed by community members. It serves the purpose of strengthening the local economy, which has taken a hit from the pandemic recession, as well as reinforcing local cultural identity. It gives visibility, both for neighbors and visitors, to the cultural artifacts that are commercialized in the village.

This is a simple example, but shows the potential for community-centered flows. The sharing of open source code enables development groups, focused on creating application ecosystems that are aligned with solidarity and collectively-owned digital territories.

Image via Portal Sem Porteiras

In South-East Brazil, the Portal Sem Porteiras Association developed an audio-soap opera produced by and for the neighborhood. As the women got together, evidence of patriarchal violence in the community was unearthed. They created a work of fiction to expose it, while also knitting together their cultural identity. The use of local references, narrators, and characters made it easy for the neighborhood to identify with the story and feel drawn to it.

In the above experiments, the most difficult part wasn’t coding these services. The challenge was content creation and communication work required to encourage the participation of community members. Content is, of course, what drives most platforms, and building a space where local content can be showcased is key for enabling a community-first experience.

It’s a completely different paradigm to explore compared to corporate platforms. It’s challenging to have people produce content for their neighbors instead of a wide general audience. It’s much more personal.

Such examples need to be replicated to other communities that seek to strengthen their women, identity, economy, self-governance—and overall autonomy. Having software and hardware platforms that enable networking between different communities that share these values can encourage this further.

Protocols created for the World Wide Web don’t take into account the possibility of local digital territories, and the possibility that these territories might not exist online today or may not need to in the future. In the past decade, the complete takeover of the Internet by corporate actors has made it obvious that the global network’s original vision of being a democratic space has been co-opted by huge centralizing for-profit platforms.

This has led to the research and development of many decentralized protocols, with the goal of distributing the web of data, as the web was originally intended, and dreaming beyond our old imaginations. As they mature, local digital territories can benefit from features of some of these distributed protocols in order to promote shared responsibility over data sovereignty and to increase data accessibility.

Some of these protocols enable data to be transported by unusual mediums, such as sneakernets (physically moving data), in ways that are secure and take privacy seriously. Making them compatible with transports that communities have come to use, such as LoRa, is also fundamental.

Last but not least, software should be performant, as efficient programs require less from the hardware, making digital machines cheaper and more accessible. Of course, inefficient coding languages such as Javascript are amazing for fast prototyping but they require more computation. That’s why some distributed protocols have been putting a lot of effort into moving their codebases to more efficient languages such as Rust or Go, if they haven’t been using them to start with.

More efficiency means less waste. An efficient stove, like a rocket stove , requires less wood and cooks food faster. Same goes for code and programs. Communities can greatly benefit from development in that direction and, as these languages develop, they become more accessible and mature.

Collective Digital Interfaces

Mobile phones have become the symbol of this historical moment. Their screens are small enough to force a one-person use of the device, yet large, bright, and colorful enough to keep a person sucked into whatever shiny thing it’s displaying. The brain’s reward pathways, mediated by dopamine, respond to screens in a very similar way to opioids .

Phones are made cheap enough to guarantee that almost any person can have one as their ultimate private property, only comparable to personal documents, toothbrushes, and underwear (which aren’t shared for obvious reasons).

Interaction with the digital world happens through our: hands, ears, mouth, and eyes. Modern phones activate these senses all in one central device, but have a limited ability to enable a collective and non-addictive experience that maintains and grows trust and solidarity within and between communities.

Electronics are becoming more modular and cheaper, and knowledge on how to tinker with them more accessible. Groups that work close to communities, such as Janastu , have done experiments with end-user devices designed for local contexts. And hardware development social-networks, such as Hackaday , have plenty of examples from around the globe with inspirations on what’s possible.

Image via Hackaday - ESP32 Walkie Talkie

Voice communication has emerged as one of the most common uses for smartphones, especially in less industrially developed parts of the world where oral cultures are common and there are lower levels of text literacy.

Text-to-speech (TTS) and speech-to-text (STT) technologies can be pivotal in crafting dialog-driven interfaces for oral-first users. By converting text into natural-sounding audio, TTS allows individuals who are more comfortable with spoken language to receive information and navigate digital spaces without the need for literacy. Conversely, STT enables users to interact with devices through their voice, making technology more accessible and intuitive for those who may find typing challenging. Together, these tools can facilitate a conversational user experience, where commands and information flow naturally as in a dialogue, bridging the gap between traditional oral communication and modern digital interfaces.

If we want to get away from phones, walkie-talkies are cheap, simple, easy to interact with and require no Internet; but they are limited by distance, the number of devices communicating, and they only work for real-time communication. An ideal device would have the best of both worlds: have a simple, sturdy body with few buttons; communicate both over the Internet through Wi-Fi, as well as other radio frequencies; and store voice messages for the familiar asynchronous (store-and-forward) experience.

This can be achieved using microcontrollers, such as the ESP32 , enabling a very low price tag, between 30 to 50 USD, making it much more affordable than most phones. Such devices can enable communication in places where no connectivity exists; as well as promote community ownership of data and a less addictive use of communication devices.

Photo by Raiz das Imagens

Television has long promoted to the masses the consumption of audiovisual content. Today the medium is transferred not through analog, but digital devices, and is an equally popular use for these devices as voice communication. The almost infinite quantity of content available through online vendors, such as Youtube, can be amazing for learning, given one knows how to filter through it.

But the popularity and accessibility of small screen devices, and the user-centered experiences of corporate platforms promote a model of media consumption based on the individual and their very specific tastes. At first it sounds like there isn’t anything wrong with that, but users’ tastes are guided by algorithms with the goals of maximizing user engagement and profit, which leads to addictive usage, creation of information bubbles, and centralization of power over data.

This individualistic way of consuming media unravels communities, but there are plenty of alternatives. By tracing the origins of video to cinema and cine-clubs, we can learn a lot about collective ways of curating and consuming content while also opening up for a process of reflection. This sort of experience enables different perspectives to be shared through an educational process, which can be much more fun than consuming content alone. All that’s required is a projector (or large screen), an open space for people to gather, and some resources on how to organize the screenings.

Image via Radio Yandê

Music and podcasts have also become an important part of our digital lives. Again, we’re drawn to self-centered ways of consuming them because of the Internet’s corporate nature. Community radios are an incredible way of bringing neighbors together and strengthening cultural identities, be it through discussing relevant topics, listening to songs together or telling stories.

Digital technology has, in many cases, created a sense that radio is a thing of the past. But there’s no reason why we shouldn’t use digital tools to create a more interactive and participatory radio experience. Analog radio stations are amazing, but the equipment can be very expensive and complex to operate. Digital radio requires only a computer, the right software, and a network connection to your listeners. It’s up to the community to choose what’s right for them.

Photo via Minimally Invasive Education for mass computer literacy

We also use digital tools for reading, writing, texting, coding, designing, planning, playing, calculating, researching… But less-industrialized places have less access to devices that are appropriate for these tasks, such as a computer with a keyboard.

Every community can have a publicly shared device so that all members can easily explore the digital world—the impact of this would be greater in low income places. Experiments such as Hole in the Wall show how powerful a public computer can be for self-learning and minimally invasive education .

People who depend on digital tools for their work would probably still need their own private device, although collective ownership should be greatly encouraged to lower the fetishism around end-user machines.

Photo via Luandro

Storage and computation devices have become widespread, with each phone today having the power and memory of super-computers of the past. For the reasons above, we should refrain from encouraging the use of smartphones for communal purposes. Instead, we can experiment with the options presented above or better yet, experiment with something entirely new.

Single-board computers (SBCs) have gained a lot of momentum in the past decade. There are loads of different options, like the popular Raspberry Pi . They are small, energy efficient, and cheap, making them great candidates for being used as community-servers.

They can be delegated the task of processing and storing data, which reduces dependency on powerful end-user devices. Making a 20 USD device, such as the Raspberry Pi Zero with a touchscreen and power supply, can be enough for basic interactions. The lower price consequently increases the accessibility to information.

Collectively managed servers enable the creation of local digital territories, where services can be curated, created, and hosted by the community itself. That’s an example of community data sovereignty, which is a fundamental topic in digital literacy, but usually too abstract to be conveyed properly without a practical case.

Collective Digital Networks

Digital experiences start with hardware. Default options are market-driven personal devices, privately controlled wired and wireless networks, and huge centralized server warehouses.

Devices and infrastructures with the goal of providing autonomy for communities must have accessibility, distribution of responsibility, and of data guardianship as priorities. Special care must be taken not to force patterns of assimilation, but rather to foster the qualities of flexibility and political creativity that were once more common in human societies. We must ask ourselves how we can recover the freedoms to move, to disobey, and to re-imagine our societies. This is essential for resisting the normalization of violence and domination.

Image via Rak Wireless

Accessible networking devices should be low-cost as well as easy to learn, use, and be appropriated by communities. A great start in this direction is the LibreRouter Project , an open hardware Wi-Fi router running open source software. It’s made by and for communities with the objective of facilitating the creation and maintenance of autonomous communication networks using mesh topologies. But it can be an overkill in cases, and many communities have limited access to financial resources.

Ideally we would develop something that’s modular. Despite being commercial, Rak’s Wisblocks are a good source of inspiration, with options of several cheap, energy efficient little wireless modules that can be assembled together like Lego blocks. We can use them to build networks using many different transport options, such as LoRa or Wi-Fi.

It would be amazing if we could have open hardware products that enable mixing different communication technologies such as high frequency radio (HF), Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM), fiber-optic cables, etc. Each of these technologies differ in levels of power consumption, bandwidth throughput, signal range, and technical and financial accessibility. Communities should be able to understand, choose, and adapt this kind of hardware to serve their collective needs.

Conclusion

The insights shared in this piece stem from our own reflections, yet they are enriched by years of exchange with various community networks, digital collectives, and organizations dedicated to local self-determination. Many of the practices we advocate for have been actively implemented, refined through experimentation, and some are in the nascent stages awaiting initiation.

It’s important to take into account that many communities might not need or want contact with the Internet or digital world. That’s quite amazing and should be valued, as these technologies are a consequence of a culture of exploitation.

But the fact is that most communities have already been exposed to the corporate web. These approaches can be used to revert the damage, hopefully assisting the turn of individualizing experiences into those of solidarity and collective construction.

A photo of Negro River rapids, Amazon, via Clóvis Miranda/Amazonastur

All that is much easier said than done, as encouraging alternatives to mainstream usage of technology is, many times, like trying to swim against a strong current. But we can build networks of communities where experiences are shared, and principles of autonomy—and livelihoods which operate in mutual relationship with Mother Earth’s complex, abundant world—can be valued and celebrated. Building these relationships with native-cultures without being extractive is fundamental for learning how to reconnect with our essence and understanding more about non-civilized practices and ways of life.

We might not be able to change the downhill course of our civilization. But we can assist in strengthening our communities so that, when crises occur, we respond with our networks from a place of autonomy, solidarity, and resilience.

Editors' Note: This piece has been edited to remove mention of a figure who has aligned themselves with violent, transphobic beliefs. We retract any reference that inadvertently signaled support of him, or affiliated groups.

Luandro is a technologist, forester, and admirer of originary cultures. Works in collaboration with communities on projects to support local autonomy and strenghten cultural identity. Active in the community-networks movement and in distributed protocols cypherspaces.

We built this little tool for you to inoculate other web spaces with the ideas and stories contained in this issue. To re-publish this piece under the terms of the license, click below to copy the markdown.